August 24th, 2025

Back to the Future – 36 Years of Sweating and Learning

Editor’s note: Only recently has CORE allowed for precise and effective heat training. We asked Coach Joe Beer to remind us what heat adaptation entailed in years past. Coach Beer has been in endurance sports since the mid 1980's. From professionals to fitness beginners he has helped thousands achieve their goals. He has written for magazines for over 30 years, has two books published, plus hundreds of articles and blogs across the internet.

The following is written by Coach Joe Beer

I have always loved to measure things, I love to test myself and learn how those numbers affect health, fitness and performance. I love to help improve athletes, myself very much included, by applying what is learned.

Heat Sessions in the 1990s

This was why the morning of Halloween 1990, in the third year of my degree, I find myself pedaling at 220 watts, in a heat chamber at 33–36°C, with eight skin temperature sensors taped on various places on my body and my core temperature being measured from, shall we say, the most accurate but most invasive location. At least this session I got to drink water. Over a litre of plain water gulped down in 30 minutes the folded lab notes in my trusty lab book now recall.

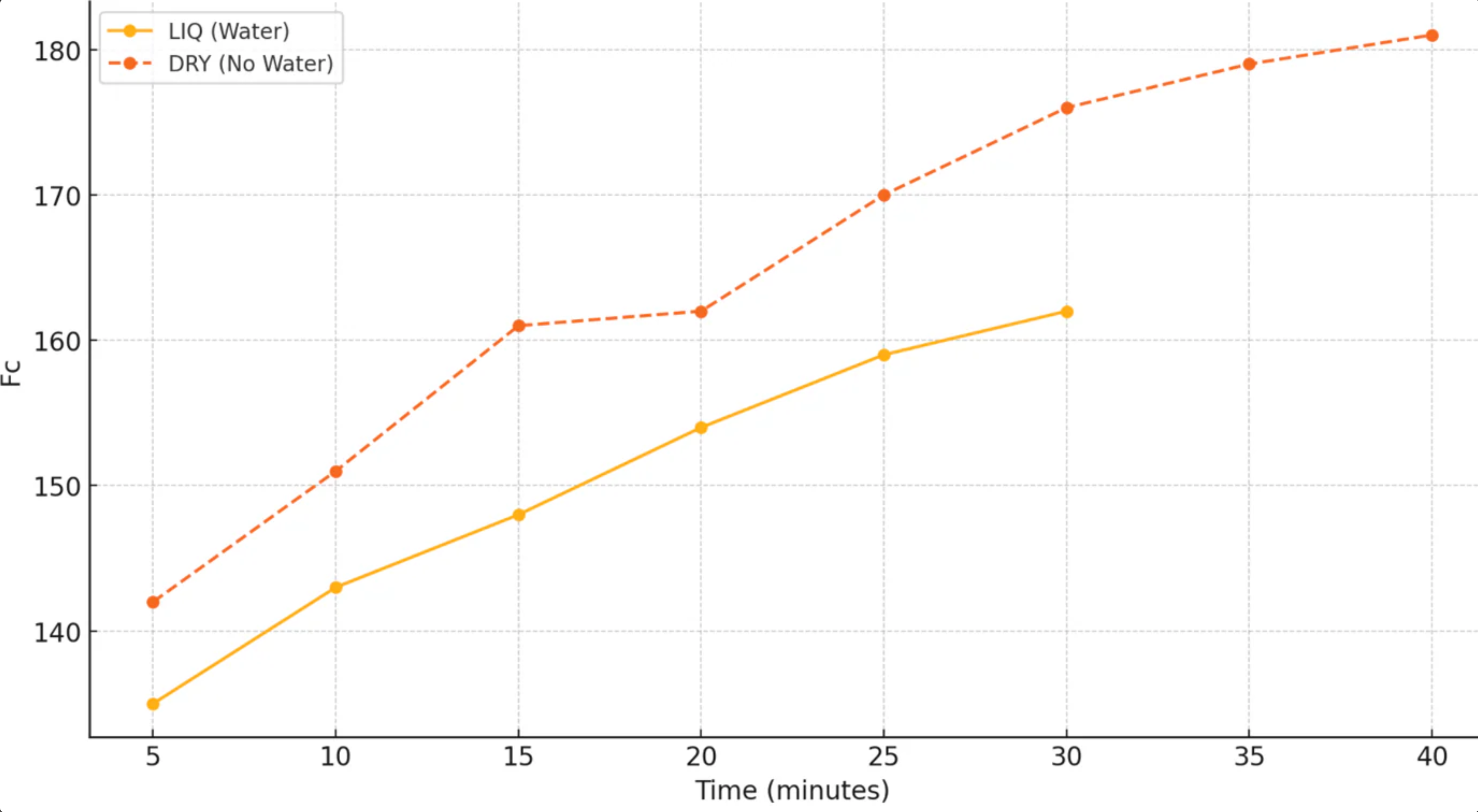

This was the second trip into the heat chamber, the previous week it was the dreaded no-water scenario in 35-36°C (that’s topping out at 96.8°F). Heart rate climbed from 142 bpm after 5 minutes riding to over 180 by 40 minutes. I had never seen above 187 in any max test so this heat exposure with no fluid was pushing my body hard, yet still only a smidge over 200 watts effort (50-55% of MaxPower) was put in at the pedals.

The sheets of notes show a spew of data recorded every 5 minutes: heart rate, temperature from every one of the skin sensors, oxygen use, carbon dioxide breathed out, mouth temperature, bike work rate, chamber temperature, breathing volume and my perceived exertion. I was a lab rat for this kind of stuff. It made the data more real to me and I got a bucketful of VO2max, lactate and even altitude data – all for the price of biking, running, arm cranking or even sitting in a very cold bath. Learning right at the coal face with some top physiologists around – I was getting every morsel of advice I could.

Heart Rate in Heat Chamber – water intake vs no water intake

And then it hit me: there were some more pages, some notes that had more heat chamber data on them. These hidden sheets revealed I was actually in the heat chamber for the very first time a full two years earlier in November 1989, as a first-year helping out some third year friends. Same gig: 45minutes cycling, 60% VO2max effort, 35°C (95°F) air temperature, no water allowed.

This first time “heat-stressed” core temperature hit 39.6°C and skin temperatures at 2 of the 7 locations topped bang-on 40 degrees. Just a shame I only have the data printout and no notes which describe the exact placement areas of the eight sensors as was properly recorded 2 years later when we did the same experiment as third years. Looking-back lesson one was keep good notes, whenever you are measuring something to be able to reflect back and use it.

These heat chamber experiments helped me learn about thermoregulation, though I could not find a control 220w ride at 20°C to compare just how high heart rate and core temp were pushed (I guess it should have been 135HR and 37.8°). The data measured then allowed neat graphs to show the stress on the body, which is useful but that was the end of the process as such. Course work-required experiment done. √

In the early 1990s, training in hot conditions was never seen as a training method for more fitness. However, if you knew that a specific hot venue required some kind of heat acclimation (e.g. Barcelona 1992) then heat training was little more than “getting used to what you will be dealing with”.

Hot weather training was just a bonus you got on training camps ensuring more motivation (i.e. sunlight) and less cold or wet weather to reduce training volume. The idea of deliberate indoor heat training to boost fitness levels and even a mechanism as to “why” this would occur – well, that was a few decades away…

Fast Forward to 2025

Leap forward three decades or so and we can now easily clip the CORE sensor onto our HR belt, tap open the phone app (that would have been science fiction to me as a twenty-something) and voila, real-time heat stress that we can measure and thus, optimise. Sometimes we want it to climb to stress us, sometimes to show we are reducing heat buildup before a key race effort, and sometimes just to see what does session or race X does to my engine temperature when conditions are A,B and C.

As a coach I use heat stress as a “measurable” that we can manipulate to improve a session’s usefulness and make the athlete faster. If you are new to CORE and heat training, read that previous sentence again. We don’t have to guess, exaggerate, wrongly manipulate or just put up with that age old complaint: “Oh, I am just not good in the heat”.

If you use a CORE sensor to measure, then you can manipulate core temperature outcomes.

If you’ve come this far, learn the key part of all of this: you really can learn to be better in the heat and heat can make you better – even at very normal temperatures

Just knowing from CORE data what a training session does to an athlete’s temperature means I can actually know truly how hot they get and make sure that easy sessions in the temperate zone are just that: easy. If we want heat training, I want to know they are really getting hot and get to know their limits. I won’t write out the comments that have appeared in athlete diaries after I have pushed them to see how hot they can deal with. But, for most, they’re the hardest sessions they have ever done. Expletives are common.

I think that the crux of why the science of heat training works is mirrored in the fatigue they all talk about at the end of the session and for a good while after (‘I’ve been unable to get a sentence together or do anything but lie on the kitchen floor and just be quiet – and that’s rare!’). You only go to a level of relatively low effort (2h @ 40% Peak Power or 60% FTP) but the lethargy and mental confusion illustrates that the heat exchange system is being pushed on an entirely different level. This is what’s behind the haemoglobin gain (as well as the mental gain of being able to say you have dealt with XX degrees).

Maybe those 1989–1990 sessions were too short; they were certainly hot but perceived exertion never got over 13. I have a hunch that longer sessions (80–120mins 2–3x week) building up more time in the 38’s per session is more time efficient and thus better for the amateur athlete that does not have so many sessions like a professional.

Practical Heat Training: Planning Prevents…

What must the everyday athlete consider in planning and implementing heat training? First off, do not do this all the time: you need not throw your fan away and dress in full winter clothing every time you indoor train on Zwift, Concept 2, treadmill or elliptical trainer. I think it helps to think of it like intervals – only really useful to find the last few percentage points, it’s not like all-year-round base training.

Second, you need to get all of your extra clothing, towels, various bottles (see box out) set up the night before. Losing time trying to find long tights or a winter rain jacket to “top off” your heat clothing misses the point – be organised. You also have more washing but that’s admin for after.

Third, I like that athletes can say what the actual room, garage, barn or kitchen temperature is for the session. This can alter the workload to ensure they get the best outcome. So get a temperature and relative humidity gauge.

Last, but very much not least, consider that these sessions take some mental grit but not in the wattage or treadmill speed you can quote on Strava or the Zwift climb time or who you kept up with. However, your raised heart rate, maybe 20–30 beats above the same workload when being cooled, well, that shows you will need a bit of time after to become compos mentis. Please, Zwift, add a function that the seat can have flames coming off it if the rider clicks “heat training”. Just saying.

Conclusion: the CORE sensor helps get heat training more specific and it works to raise your ability to deal with heat adversity and at the same time boost fitness due to the greater haemoglobin mass. I have never shied away from heat. I like it, but the 1990s kid from that lab would have loved the way CORE can measure internal temperature from the skin (phew) and allow cooling, optimising or pushing heat as a new (more than) marginal gain.

Heat is also now being seen as a way to help recovery, but that’s for another time…

Train smart.

JB

About Joe Beer

Coach Joe Beer has been in endurance sports since the mid 1980's from 10k’s and half marathons came the Bath Triathlon and eventually Escape from Alcatraz Triathlon, The Ironman World Championship in Kona Hawaii to time trails, London to Paris charity cycles, Ultra runs and most things in-between.

Joe uses his Health, Fitness and Performance model to help those wanting to lose weight or finish an Ironman. From professionals to fitness beginners he has helped thousands achieve their goals. He has written for magazines for over 30 years, has two books published plus hundreds of articles and blogs across the internet. Look out for his podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and other platforms.

Joe practices what he preaches with aerobic sessions, heat training, weights, key workouts to power and the odd competition alongside his partner Debbie. There’s talk of a 100-mile run.

He is constantly learning how to be healthier, fitter and perform in challenges and passing experience onto others. He works with top clothing company NOPINZ, known for innovations such as the SUBZERO indoor racing suit and the game changing aero SpeedPocket.